The Squat should be a standard exercise in any lifters program. Whether the goal is strength, hypertrophy (increase in muscle size), increased accelerative ability, or a heightened vertical jump, the squat is the tool for the task. In addition to working the muscles of the legs, hips, lower back, abdomen, and obliques, the demands of squatting should stimulate a growth response from the body that will carry over into strength and size increases in other areas.

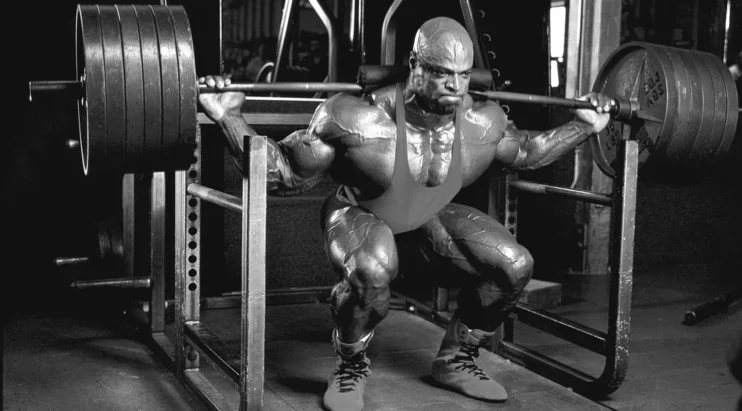

The basic technique of the squat consists in placing a loaded barbell across the shoulders, then bending at the hips and knees, descending into the bottom position, “the hole,” and returning to an erect position. We will examine the squat from the deck up.

Stance

This varies from individual to individual, but one thing is necessary for all who wish progress: you must keep your feet flat on the deck at all times. The center of gravity may be maintained over the center of the foot, but it is generally best to push through the heels. This will help in maintaining bar position and help eliminate a small degree of forward lean. To achieve this, some people find it necessary to curls the toes upward while squatting, forcing their heels flat. The feet should be placed at least shoulder width apart, and some individuals may best utilize a stance nearly twice shoulder width. The narrower stance tends to place more direct emphasis on the quads, and creates a longer path for the bar to travel.

The wider stance (often called “sumo”) tends to be favored by many powerlifters, although some have enjoyed great success with a relatively narrow stance. The sumo stance place more emphasis on the adductors and hamstrings. As a rule of thumb, lifters with longer legs will need a wider stance than shorter individuals. However, there are exceptions. A wider stance will tend to recruit both the adductors and buttocks to a greater degree than a narrow stance.

The shins should be a close to vertical as possible throughout the entire movement. This lessens the opening of the knee joint, and reduces the shearing force as well. By reducing the workload that the knee joint is required to handle, more of the work is accomplished by the larger muscles around the hip joint. For powerlifters, this decreases the distance one must travel with the bar, as the further the knee moves forward, the lower the hips must descend to break parallel.

There are several schools of thought on squat depth. Many misinformed individuals caution against squatting below parallel, stating that this is hazardous to the knees. Nothing could be further from the truth. Stopping at or above parallel places direct stress on the knees, whereas a deep squat will transfer the load to the hips, which are capable of handling a greater amount of force than the knees should ever be exposed to. Studies have shown that the squat produces lower peak tibeo-femoral (stress at the knee joint) compressive force than both the leg press and the leg extension.

For functional strength, one should descend as deeply as possible, and under control. (yes, certain individuals can squat in a ballistic manner, but they are the exception rather than the rule). The further a lifter descends, the more the hamstrings are recruited, and proper squatting displays nearly twice the hamstring involvement of the leg press or leg extension. and as one of the functions of the hamstring is to protect the patella tendon (the primary tendon involved in knee extension) during knee extension through a concurrent firing process, the greatest degree of hamstring recruitment should provide the greatest degree of protection to the knee joint.

When one is a powerlifter, the top surface of the legs at the hip joint must descend to a point below the top surface of the legs at the knee joint. Knee injuries are one of the most commonly stated problems that come from squatting, however, this is usually stated by those who do not know how to squat. A properly performed squat will appropriately load the knee joint, which improves congruity by increasing the compressive forces at the knee joint.

Which improves stability, protecting the knee against shear forces. As part of a long-term exercise program, the squat, like other exercises, will lead to increased collagen turnover and hypertrophy of ligaments. At least one study has shown that international caliber weightlifters and powerlifters experience less clinical or symptomatic arthritis. Other critics of the squat have stated that it decreases the stability of the knees, yet nothing could be further from the truth. Studies have shown that the squat will increase knee stability by reducing joint laxity, as well as decrease anterior-posterior laxity and translation. The squat is, in fact, being used as a rehabilitation exercise for many types of knee injuries, including ACL repair.

One of the most, if not the most critical factor in squatting is spinal position. It is incredibly important not to round the back. This can lead to problems with the lower back, and upper back as well. The back should be arched, and the scapulae retracted, to avoid injury. This position must be maintained throughout the entire lift, as rounding on the way up is even more common than rounding on the way down, and people who make this mistake are the ones who perpetuate the “squats are bad for your back” myth.

Furthermore, spinal position is essential to maintaining a proper combined center of gravity (CCOG). The farther one leans forward or, even worse, rounds the back, the more strain the erectors are forced to bear, and the less the abdominals can contribute to the lift. To say nothing of the fact that the greater the lean, the greater the shearing force placed on the vertebrae. Proper spinal alignment will assist in ensuring that the majority of the force the spine must bear is compressive in nature, as it should be.

Another reason for descending below parallel is that the sacrum undergoes a process known as nutation (it tilts forward, relative to the two ilia on either side of it). At only 90 degrees of knee flexion, the sacrum is still tilted backward, which inhibits proper firing of the erectors and gluteus maximus and minimus. Going through a full range of motion completes the rotation of the sacrum and allows maximal muscular recruitment.

“Squats are bad for your back” is yet another cry of the weak of both leg and spirit. While an improperly performed squat can cause problems, so can improperly performed barbell curl, yet many of the people who use the squat rack only to curl do not seem to have a problem strengthening their elbow flexors. While the squat can be hazardous to the back among the untrained who often incline the torso to an unsafe degree, as well as round the back, skilled athletes have been shown to minimize trunk segment torques by maintaining a more erect posture.

It has been positively shown that maintaining an upright torso during the squatting motion reduces both spinal compression and shear forces. Several studies have shown that weightlifters experience not only less back injury and pain that many other athletes, but often even less than inactive individuals, which clearly displays that a proper weight training program, which includes squatting, is beneficial in avoiding injury.

The placement of the bar is another very important consideration when squatting

If one places the bar high on the traps, more emphasis will be placed on the quads, and a low bar squat recruits more of the lower back and hamstrings, by virtue of back extension, simply because the lower the bar is placed, the greater the degree of forward lean. Even when high bar squatting, the bar should NEVER be placed on the neck. This is far more stress than the cervical vertebrae should be forced to bear.

When a powerlifter squats with a low bar position, the bar should be placed no lower than three centimeters below the top of the anterior deltoids. For other lifters, comfort and flexibility will go a long way towards determining bar positioning. When gripping the bar, at first it is best to place your hands as close together as possible, to maintain tension in the upper back, and to avoid any chance of the bar slipping. As a general rule, the lower you place the bar, the wider your hands will have to be. Anything placed between the bar and the lifter, such as a pad or towel, decreases the force of friction and increases the chance of the bar slipping. It is to avoid injuries that this practice is banned in competition. Also, this will artificially raise the lifter’s CCOG, which makes it harder to balance under a heavy load.

Look slightly upward when squatting, to avoid rounding the upper back. The movement should be initiated from the hips, by pushing the glutes back, not down. This will assist in keeping the shins vertical. On the way down, keep the torso as close to vertical as possible, continue to push the hips back, and push the knees out to the sides, avoiding the tendency to allow them to collapse inward. The manner in which the lifter descends will greatly influence the manner in which the ascent is made. When the necessary depth is achieved, begin ascending by pushing the head back, and continue to concentrate on pushing the knees outward.

One of the most common mistakes made while squatting, or performing any exercise for that matter, is improper breathing. At first, the lifter should inhale on the way down, and exhale on the way up. Many advanced lifters will take several large breaths, hold it all in on the way down, and then exhale forcefully at their sticking point on the way up. This technique, known as the “Partial Valsalva,” requires practice like any other.

There are many other types of squats, but all of them are secondary to the squat itself, which is appropriately termed the “King of Exercises.”

The front squat is performed in a similar manner, but the bar is held in the clean position, across the anterior deltoids, not the clavicles. The hands should be slightly wider than shoulder width, and the elbows should be elevated as much as possible. The bar is maintained as high as possible by elevating the elbows. This allows the lifter to maintain a more upright posture, and increases the emphasis on the glutes, while lessening the involvement of the lower back.

This exercise may allow a lifter who lacks the flexibility required to perform a full squat achieve a reasonable depth while improving flexibility. The front squat will place far more emphasis on the quadriceps muscles and less recruitment of the hamstrings takes place. When comparing the squat to other exercises, it is important to note that the squat causes less compressive force to the knee joint, and greater hamstring activation, than both the leg press and the leg extension.

Another popular type of squatting exercise is the split squat (“lunge”). In this type of squat, the legs are placed at approximately shoulder width, but one foot is out in front of the athlete and one is placed to the rear, as if a lifter has just completed the jerk portion of the clean and jerk. The athlete descends by bending the front leg until the knee is slightly forward of the toes. The shin of the front leg should be ten degrees past perpendicular to the floor. It is important to maintain an upright posture when doing so. As when squatting, co-activation of the hamstring serves to protect the knee joint during flexion, which is very important as often a greater degree of flexion will occurring when performing the split squat.

Certain misinformed and so-called “personal trainers” will have people squat in a smith machine, which is, quite simply, an idea both hideous and destructive. This is often done under the misguided “squat this way until you are strong enough to perform a regular squat” premise. Even if one overlooks the obvious fact that it is better to learn to do something right than build bad habits from the start, there are numerous other factors to be considered.

The smith machine stabilizes the bar for the lifter, which does not teach the skill of balancing the bar, balance being important to any athlete, as well as the fact that free weight squatting strengthens the synergists which goes a long way to preventing injuries. A chain is only as strong as its weakest link, and the smith machine leaves far too many weak links. To say nothing of the fact that free weights provide a greater transfer of functional strength than machines.

Furthermore, the bar moves straight up and down, and very few people squat in this manner, which means that the smith machine does not fit a lifters optimal strength curve. The smith machine also requires that the lifter either squats with his torso much closer to vertical than would be done with a real squat, which mechanically decreases the involvement of both the spinal erectors and the hamstrings. While this would be fine if it was done by the lifters muscular control, when the smith machine does this it is disadvantageous to the lifter by virtue of decreasing the ability of the hamstrings to protect the knee joint.

Another mistake made, aside from simply using it in the first place, is allow the knees to drift forward over the toes, the chance of which is increased by the smith machine. As was previously mentioned, this greatly increases the shearing force on the knees. This from a device touted by the ignorant as “safe.”

There is a great debate about the use of belts when squatting, some sources insist that you must wear one, while others state quite the opposite. It is worth noting that there are plusses and minuses to wearing one. Using a proper belt while squatting can serve to increase intra-abdominal pressure (IAP) which will serve to stabilize the spinal column, reducing compressive forces acting upon the spine and reducing back muscle forces.

However, muscle activity of the trunk appears to be significantly reduced when using a weight belt, which can lead to the muscles of the trunk receiving a less than optimal stimulus when using a belt. Other proponents of belt use have shown that the use of a properly designed power belt may improve a lifter’s explosive power by increasing the speed of the movement without compromising the joint range of motion or overall lifting technique.

There are numerous methods of utilizing the squat in any athlete�s training program. While a variety of rep and set ranges are optimal for a bodybuilder who wishes to maximize hypertrophy, an athlete’s must carefully plan a training program to meet their goals. Even though squatting will lead to gains in size, strength, and jumping ability, the more specific the program, the greater the results. When an untrained subject begins lifting, numerous programs produce gains in practically all areas, but this changes rapidly, with limited progress being made unless something is altered.

To utilize the squat to gain in size is both simple and complex. Individuals will respond to a variety of rep ranges in different manners based on fiber type, training history, biomechanics, injuries, etc. Bodybuilders, who are concerned exclusively with gains in size, should squat heavy, as fast-twitch muscle fibers have the greatest potential for hypertrophy.

However, sarcoplasmic hypertrophy (growth of muscle tissue outside of the sarcoplasmic reticulum) will contribute to overall muscular size, and is obtained by training with lighter weights and higher reps. Rate of training is once again an individual decision, but as a general rule, the greater the volume of training, including time under tension (TUT) per workout, the longer one must wait before recovery is optimized, allowing super compensation to take place. A word of caution about performing higher repetitions while squatting: As the set progresses, the degree of forward lean increases. While this is desirable to increase the stress on the hamstrings, it takes the emphasis off of the quadriceps, as well as increases the risk of injury.

An athlete wishing to improve his vertical jump should not only squat, but perform a variety of assistance work specific to both improving squatting strength as well as specifically improving jumping skill. As jumping requires a great expenditure of force in a minimal amount of time, exercises such as squatting should be performed to increase muscle power, as muscle cross-sectional area significantly correlates to force output. When wishing to increase one’s power through squatting to assist in the vertical jump, one must train to generate a high degree of force.

This is done by squatting a dynamic manner, where one is attempting to generate a large amount of power while using sub maximal weights. This has been shown to provide a great training stimulus for improving the vertical jump. A program consisting of a session once-weekly heavy squatting, ballistic lifting, and plyometric training, with each being performed during a separate workout, should provide maximal stimulus while allowing maximal recovery and supercompensation.

When training to improve one�s overall squatting ability, expressed as a one-repetition maximum (1rm), once again a variety of programs may be utilized. The most common is a simple periodized program where, over time, the training weight is increased and the number of repetitions decreases. This sort of program is utilized by both Weightlifters and Powerlifters alike. A sample periodized program is included in Appendix B. Some sources state that you must train to failure, while others state that one should train until form begins to break down, leaving a small reserve of strength but reducing the risk of injury. It should be stated that there is no evidence that indicates training to failure produces a greater training stimulus than traditional volume training.

Far and away the most complicated, and controversial training program is the conjugate training method. Using this method one trains to develop maximal acceleration in the squat during one workout, and in another workout (72 hours later) generate maximum intensity in a similar exercise to the squat. This is based on an incredibly lengthy study by A. S. Prelepin, one of the greatest sports physiologists of the former Soviet Union. This method also uses the practice of compensatory acceleration, where an athlete attempts to generate as much force as possible, by not only generating maximal acceleration, but by continuing to attempt to increase acceleration as the lifter�s leverage improves.

The addition of chains or bands can increase the workload as well as force the athlete to work harder to accelerate the bar. Utilizing this system, the squat is trained for low repetitions (2) but a high number of sets (10 � 12), with training intensities being 50 � 70% of the athlete�s 1rm. Rest periods are short (45 � 75 seconds), and the squats are often performed on a box, which breaks up the eccentric-concentric chain, and inhibits the stretch reflex, forcing the athlete to generate the initial acceleration out of the bottom of the lift without the benefit of the elasticity of the muscle structure.

During the second workout, an exercise which taxes the muscles recruited when squatting, but not an actual squat, is performed for very low repetitions (1-3, usually one). The goal on this day is to improve neuromuscular coordination by increased motor unit recruiting, increased rate coding, and motor unit synchronization. This allows the athlete to continue to generate maximal intensity week after week, but by rotating exercises regularly optimal performance is maintained.

For one micro cycle, a squat-like exercise is performed, such as a box squat, rack squat, or front squat is performed, then the athlete switches to a different type of exercise, such as good mornings, performed standing, seated, from the rack, etc. for another micro cycle, then switches exercises again, often to a pulling type exercise such as deadlifts with a variety of stances, from pins, from a platform, or any number of other variations. Once again, chains or bands may be added to increase the workload. A sample training program is included in Appendix B, and a variety of maximal effort exercises can be found in Appendix C.

Assistance work for the squat is of the utmost importance. The primary muscles which contribute to the squat, in no particular order, are the quadriceps, hamstrings, hip flexors/extensors, abdominals, and spinal erectors. When an athlete fails to rise from the bottom of a squat, it is important to note that not all of the muscles are failing simultaneously. Rather, a specific muscle will fail, and the key to progress is identifying the weakness, then strengthening it. A partial list of assistance exercises is provided in Appendix D.

While it is impossible to simply state that if x happens when squatting, it is muscle y that is causing the problem, some general guidelines follow. If a lifter fails to rise from the bottom of a squat, it generally indicates either a weakness in the hip flexors and extensors, or a lack of acceleration due to inhibition of the golgi tendon organ (no stretch reflex � train with lighter weight and learn to accelerate if this is the case). If an athlete has a tendency to lean forward and dump the bar overhead, it generally indicates either weak hamstrings or erectors. If an athlete has trouble stabilizing the bar, or maintaining an upright posture, it is often due to a weakness in the abs.

The above factors assume that proper technique is being maintained. If this is not the case, no amount of specific work will overcome this problem. Drop the weight and concentrate on improving skill, which is far more important than training the ego, and less likely to lead to injury.

Safety is the key issue when squatting, or performing any lift. With a few simple precautions, practically anyone may learn to squat, and do so quite effectively. The rewards are well worth the effort. Squat heavy, squat often, and above all, squat safely.